The red-shaded block is the Seneca Indian Cemetery. The green-shaded structure is the Tolliver house. Fields Avenue had not yet been created but would run along the line of the blemish on the map between the referenced cemetery and house.

2006 Google Eart map of the same location. The former cemetery is now the Seneca Indian Park. The green shaded area is approximately where the Tolliver house was located.

Buffalo Courier-Express October 13, 1940

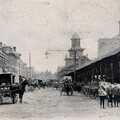

Landmark of Indian Days to Pass from Scene

Century-Old South Buffalo Home was Center of Reservation

Runaway slave, white wife occupied dwelling during days of Red Jacket

by Walter McCausland

The Tolliver House, landmark of early Buffalo, which has stood for many years in Fields Avenue near Indian Church Road, soon will fall to the wrecker's ax.

Built more than a century ago by Humphrey Tolliver, reportedly a runaway slave, the house stood for decades in the heart of the Seneca Indian Reservation. Here in the woodlands far from the hustle and bustle of the little village of Buffalo, which was just beginning to recover from its destruction by the British in 1813, Tolliver and his white wife found the peace and quiet they sought, reared a family of twelve children, tilled their garden tract, and earned the respect of the Senecas.Nearby was the cabin of Red Jacket, its exact site lost to history. The old Indian burying ground received his body in 1830. Not far away, Mary Jemison, White Woman of the Genesee, spent the last two years of her life, and here she too was buried.

Just a stone's throw away from the Tolliver home, the Christian Senecas in 1829 built the church that gave Indian Church Road its name. Here, two years later, came the Rev. Asher Wright to work among the red men. From his own press, set up in the new Mission House in what is now Buffum Street, he issued the Mental Elevator and other publications in the Seneca language.

Today all is changed. Woodlands gave way to farmlands, which later bowed to real estate developer and builder. The city has absorbed the reservations. Old chiefs and tribes are gone. Even the bodies of those buried in the nearby cemetery were removed to Forest Lawn, and the feet of children at play scamper today where once they slept. The coffin of Mary Jemison has been taken to Letchworth Park. The Indian church is gone; the Mission House replaced by School 70. Only reminders of the romantic are a few names - Seneca Street, Indian Church Road, Indian Orchard Place - and the old Indian Burial ground now a part of the city park system through the generosity of John D. Larkin, and the old Tolliver house.

Of Tolliver, surprisingly little is known. He died in 1881, in the house he had built, leaving his wife, two daughters and three sons - Jennel and Nancy, Dealy, Jerry and Zach. According to old-timers, Tolliver was about 87 when he died. This would indicate he was born about 1794.

Family records were lost in a fire years ago, but descendents say he was born in Bath and that it was there he met and married a girl named Nancy Ann Carl, whose mother had died on a ship while en route to America. Their marriage was an unusually happy one, and throughout their long life Tolliver showed her the utmost solicitude. They were a familiar sight in the neighborhood, Mrs. Tolliver invariably wearing a heavy veil as protection against the stares of the curious.

They had come to Buffalo when Tolliver was about twenty, presumably about 1814, after he had served as chef on a lake boat. Whether he had ever been held in slavery is not clear; but he hated the institution implacably.

"Two things I want before I die," he used to say. " I want to get my hands on the man who sold my father and mother into slavery and on the man who bought them."

Had such a meeting occured, the consequences could easily have been imagined. Tolliver was renowned for his powerful physique. A woodsman who swung at ease a 7 1/2 pound ax, he is described as six feet two inches tall, lean and muscular. Hunting and fishing occupied much of his time and that of his sons. Many an old resident remembers his fishing-nets drying on the fence around the burying ground.

So far as history is concerned, only one passing reference to this picturesque pioneer is known. In Volume III of the transactions of the Buffalo Historical Society, W.C. Bryant wrote:

"Humphrey Tolliver, an aged runaway slave from Virginia, with his white wife and mulatto children, occupied a cottage, and cultivated a few acres of garden land bordering the cemetery grounds.

"He had lived there many years - when Red Jacket was in his glory and the leader of his people. He continued to reside there long after the last Seneca turned his back upon the ancient seat of his tribe, never more to return. Thereafter, Tolliver became the self-appointed sexton of the old graveyard when the crowd of white immigrants surged in to fill the places of the departed Senecas, and he buried the pale-faced dead in the holy ground which had been consecrated as the place of sepulture of the red men.

"Neve could he be induced, however, to consent that the sacred area, about the walnut tree, should be profaned by the spade of the grave-digger. He would shake his gray head and say, The big men of the Senecas were buried there. He knew them well, those silent, composed, and mysterious men, in strange, picturesque garb and speaking an incomprehensible language. He died a few years since at an advanced age, and a new custodian of the Indian cemetery - a white man who lacked sensibility and was superior to the weakness of superstition - succeeded to the humble office."

The Tolliver house stood north of the burying ground, within the lines of present Fields Avenue. It was moved to its present location when that street was cut through. Originally it was surrounded by apple and cherry trees with a long white grape arbor runing to Indian Church Road. What arrangements were made with the Indians when the house was built no one knows; but Tolliver did not acquire title to the land on which it stood until 1849. Shortly after the death of Tolliver's wife in 1887 the property was acquired by Allen D. Strickler, whose estate now holds the title.

The earliest deed, dated September 12, 1810, conveys all rights, title and interest of Wilhelm Willink and others (the Holland Land Company) to David A. Ogden, "subject to the rights of the native Indians." By treaty dated January 15, 1838, the Seneca Nation conveyed an interest in the reservation to Thomas L. Ogden, and Joseph Fellows for $202,000.Frederick Houghton in his History of the Buffalo Creek Reservation, states that of this sum, $100,000 was to be invested for the Seneca Nation by the President, and the remaining $102,000 was to be paid to the owners of improvements on the lands.

The Indians were divided as to the wisdom of the sale which, if consummated, would require them to move from their ancient reservation. Long discussions followed. Houghton records that it was not until December 28th that negotiations were concluded, and the treaty with the signatures of 41 alleged chiefs was transmitted to President Andrew Jackson. Both the President and the Senate were doubtful of its validity, but it finally was ratified March 25, 1840, and proclaimed by the President April 4th. The Senecas then began vigorous efforts to have it annulled; and the situation was not ironed out until a new treaty was negotiated in 1842.

Tradition has it that Tolliver and his wife prepared and served the banquet that accompanied the signing of one or the other of these two treaties.

For many years after the Indians had moved to the Cattaraugus Reservation, they returned frequently to the sacred burying ground and to visit Tolliver and his family. They would camp a the foot of Buffum Street, bringing basketry and other handiwork for sale to the palefaces who now occupied the land. Gradually these pilgrimages became less frequent; but even in recent years an occasional solitary old brave has paid a quiet reminiscent visit to the site of the busy tribal life of a century.

For more information on the Seneca settlement in South Buffalo, see "The Seneca Indian Park, " by John H. Conlin, in the Fall 2004 WNY Heritage Magazine.