The text below was written by Ellen Taussig (1906 - 2005), a reporter for the Buffalo Evening News for 25 years until she retired in 1974. When she wrote her 1986 memoir, "Wings On My Heels: A Newspaperwoman's Story," she included excerpts from articles she wrote during her career, of which this is one. Though originally from Philadephia, Miss Taussig became a Buffalonian, living here for over 40 years. And she observed that the wave of demolition which occured in the name "urban renewal" was changing her city in fundamental ways.

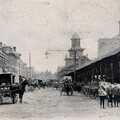

The black & white photos accompanying her story are from the Library of Congress Historic American Buildings Survey; they were taken in 1965.

Renewal is a fresh, spring word that is echoing down the streets of most U.S. cities. In its wake, some of the very structure and tradition of a city falls. Only time will tell if renewal justifies itself.

In every city there is what might be described as a heart or core. The Erie County Savings Bank at Shelton Square was perhaps the primary valve in the heart of downtown Buffalo, the McKinley Monument rising in a circular park in the center of town excepted. But the Erie County Savings Bank was the living heart.

I wrote her eulogy:

A Buffalo duchess will soon return to the dust. Arched of brow (windows), ornamental of coiffure (turrets), and buxom of figure (granite walled), the old Erie County Savings Bank Building will bow to progress.

For 74 years, this temporal grande dame, whose style of architecture is Romanesque Revival, has shared winds on her roof, snows in her eyes, and pigeons on her balustrades with her spiritual neighbor, St. Paul's Cathedral.

Side by side on separate triangles, which are unique characteristics of downtown Buffalo, they have stood.

By May 1, the 15 remaining tenants of a one time

60 in the building will have vacated her spacious, towered offices and

travertine stone, Mexican mahogany-wainscoted halls, leaving her hollow.

The last retreating footsteps will have echoed down her nine-story marble

staircase, with its bronze balustrade featuring the fleur-de-lis of royalty.

That golden opulence of the bank proper, into which three

generations of Buffalonians have walked to deposit or withdraw the material

fruit of their lives, will be darkened, its Moorish mellowness deserted, its

gold leaf ceiling dimmed, its autumnal-toned marble pillars left guarding only

emptiness.

Silent will be the two great marble clocks which for years have

ticked off accruing interest. The bronze lamps in the customer's desks will be extinguished, and

the bronze wastepaper baskets will stand empty of ripped open pay envelopes.

Her tills, coffers and vaults unloaded, the duchess - relieved of

responsibility - will figuratively breathe a deep sigh - and wait.

Already the shadow of her demise looms in the distance. A giant

crane, like the one which will batter down her walls, rests in the adjoining

Main Place excavation (hub of the renewal effort), of which she will become a

part.

Why? hundreds of Buffalonians asked. One gets numerous answers.

The need to do something in the downtown core area to improve it.

More efficient operation of the bank which, as it had expanded in

the last 15 years, had been obliged to take over space in numerous locations

throughout the building.

The tile is crumbling. Valuable space wasted owing to turrets and odd corners. The plumbing is vintage 1893. Thomas Edison helped plan the electrical system, but today it's inadequate. A ravenous breed of summer mite has invaded the banking floor for

many years, and still 'outwits' the best professional exterminators.

Air conditioning installed in 1937, the heated sidewalk of 1957,

undersized elevators obtained in 1925, and an 8-year-old gas furnace all need

rehabilitation 'to be made operable at today's norms.'

(The duchess tosses her turrets at the word

'norm.' Designed by George B. Post, architect for the Equitable Bldg., New

York, first office building in the metropolis to have an elevator; the Produce

Exchange; the Stock Exchange and the buildings of the College of the City of

New York - decorativeness rather than normality has been her forte.)

Harold L. Olmsted, well-known artist and architect, who had done

his best to save the duchess, understood: 'The whole place, upstairs and down,

reeks with honesty and open-minded intelligence from its delightful pavement

blocks to its heavily paneled doors and wainscots, its lovely windows and the

views they so adequately and amusingly frame...its charming variance in plan

from the usual.'

But there were other voices:

"If it were the Tower of London, it could support itself as a tourist's

attraction." Harlan J. Swift, the duchess' eighth president, said in part,

in a letter to friends of the bank. "But it is not, and cannot support

itself as anything except a beloved landmark of a bygone era in Buffalo

history."

The eulogy continues:

The Erie County Savings Bank Building has always been different

from most banks in the area.. Continential in appearance, its atmosphere is

that of a place where large affairs are conducted in a dignified manner.

Next to pigeons, law firms - some with four or five-member titles,

i.e. Moot, Sprague, Marcy, Landy & Fernabach, have been its prinicipal

tenants.

It's 'Good morning, Tom,' or 'How do you do, Sir?' not a 'Hello,

Charlie,' in the elevator, sort of place. No slapdash or chatting with the

elevator girls. Decorum, and above all, permanence.

In the cellar of the bank one feels fortressed. Descending to it,

down slate steps wavy with age, one reaches the boiler room, the heart of the

duchess.

"This building was made," says Miltion W. Treach,

superintendent and chief engineer..."You'll never see another building

like this."

The bank walls are nine feet at the base and taper up to three

feet. Great brick arches span the distance between the four massive pillars

which support the middle of the building, and huge boulders stud the stone and

brick foundation at intervals. Overhead is a spaghetti of multicolored pipes.

Mounting to the ninth floor, turret windows give on a fascinating

upheaval of tiled roof, carved stone images and finials, where, as on a

mountain, the snow lingers in the crevices long after the pavements below are

cleared.

And so in mid-summer of 1967, the ravaging of

the duchess began.

Edward E. Gabriel, president of the Niagara Wrecking & Lumber

Co., foresaw no difficulty in the task: "We have the original working plans," he told me,

"and it's just a question of working in reverse." (That's what he

thought.)

"She just doesn't budge," noted George L. Sheridan, a

vice-president of the bank in charge of her. Nevertheless, the grand old building already had experienced a

foretaste of what was to come.

"When they drove the sheet piling under our north side during

the Main Place excavation, however, she shivered with every wallop of the pile

driver," recalled Mr. Sheridan.

They held an auction of the duchess' fittings in

June. At first they could not sell the magnificent marble staircase (about 180

steps) with its wrought iron balustrades, because they needed it to climb from

floor to floor. But they sold practically everything else, from the monogrammed

brass doorknobs which locked on both sides and had discreet keyhole covers, to

the marble walls and flooring.

One could feel the pressure of time throughout the sale, the hurry

to get her down. Utility and removability rather than craftsmanship were the

determining factors of purchase.

The ratio of time, money and a craftsmanship (which has practically

vanished) it took to build her, to the prices they paid for the baroness'

entrails was traumatic to witness.

The great mirrors on the banking floor went for $5 each; they

gouged out the 2-1/2 ton main vault for a $1,000 bid, and the big Victorian

mailbox in the lobby brought $10.

"It's this way," said Auctioneer Rosen, "this is old

stuff. A man pays $1 for something, and he has to hire labor at $4.50 - $5.00

an hour to get it out."

The duchess refused to give up her heart - the 15-foot gas furnace

(kept at 80 pounds constant blood pressure in winter), and the auxiliary coal

one that could be stoked up to 120 pounds.

Eventually they were sold for scrap. She was now ready for the wreckers.

The lions above the Niagara Street entrance were saved and now can be seen on the Buffalo State College campus.

The duchess did not bow easily.

Every evening for more than three months a battle was fought in

Shelton Square between her and two cavernous cranes. The latter attacked with

two primitive means of offense: A pair of jaws and a rock - or in modern

wreckers' parlance - a clambucket and a busting ball. The former weighed in at

3 tons, the latter at 3-1/2.

The fight was one of the toughest in veteran wreckers' memory. For

a wrecker to admit resistance is like a weight lifter confessing his muscles

are getting flabby.

It began at 4:30 in the afternoon and continued through 7:30 the

next morning, five days a week. A crowd of variable size would gather to see

the kill. It was the show of the town. Whole families arived in station wagons

from the suburbs. A middle-aged couple might bring chairs. A friend would

explain to a blind man what was happening.

As Mr. Gabriel had said, the original plans of the building were

made available. When the crane operations of the 25-man demolition crew began

to munch at the building, however, it was evident that plans and reality did

not agree.

The roof with its turrets and gargoyles and finials was the

toughest. A finial lifted intact like a birthday candle to the ground measured

3-1/2 feet high and weighed an estimated 600 pounds. Not to mention the cones

on the towers which looked like cake frosting aloft, but on the ground measured

20 feet high and 15 feet across. Cast iron and steel.

As the wrecking progressed, scores of 200-pound red granite carved

images, 5-feet thick, set in the walls around the crest of the building came

tumbling down, their carnival faces of joy and sorrow biting the dust. The very

stones of the building were resistant. The walls, which tapered from nine feet

at the base up to three feet, were composed of foot-thick red granite stones

weighing up to three tons each. Interlocked, they had to be lifted out like lumps

of sugar, piece by piece. They did not sound like sugar when they dropped.

The evening before the opening of the Mall, of which the new streamlined Erie County Savings Bank towered at one end of Shelton Square, I was walking up Main Street when I caught a glimpse of history. It's a winged thing, and you have to catch it on the fly; you can easily miss it. But as I came closer to the new building, I saw a man sweeping up the pavement with a brush. He was an Indian whose ancestors, a hundred years before, had sold sassafras, arbutus and violets here, on Shelton Square. Now in the shade of the new, modern bank, with its flat roof, its central heating, its adequate electrical system and its modern plumbing, he was sweeping up the last of the duchess' dust - and the past, in the wake of renewal.

The Erie County Savings Bank lions in place at Buffalo State College. The left lion's shield displays the bank's 1854 incorporation date; the right lion's shows the building's 1893 construction date.

Brief History of the Erie County Savings Bank

The bank incorporated on September 1, 1854 and, after setting up at a temporary location, moved to Main and Erie Streets where it operated for ten years. In 1867, the bank constructed its first building at Main and Court Streets. In 1889, the move of First Presbyterian Church to Symphony Circle made its Main/Church/Niagara location available, and the Erie County Savings Bank purchased the property. The Bank featured here was constructed from 1890-1893; its $1,000,000 cost was paid from bank profits. The building stood until 1967 when it was demolished as its new headquarters was constructed a stone's throw away at One Main Place (Main Place Mall). A decade after moving into its new building, the bank changed its name to the Erie Savings Bank (1977) and in 1981 became a federally-chartered savings bank, Erie Savings Bank, FSB. In 1982, its name changed to Empire of America, aka "The Big E." The bank, having expanded after 1981 and acquiring troubled savings and loans institutions, failed in 1989 and was taken over by the federal Resolution Trust Corporation in January 1990. After M&T and KeyBank acquired its remaining deposits two years later, the bank disappeared into history.